For those unaware of my Top Ten By Year column:

I pick years that are weak for me re: quantity of films seen. I am using list-making as a motivation to see more films and revisit others in a structured and project-driven way. And I always make sure to point out that my lists are based on personal ‘favorites’ not any notion of an objective ‘best’. I’ve done 1935, 1983, 1965 and now 1943. Next I’ll be doing 1992.

I’m going to keep this intro short because my write-ups ended up being way longer than I’d anticipated. It’s been so insightful spending time with 1943. Hollywood during WWII is endlessly interesting, if not so much for the output as a whole (though there’s lots of great stuff as always), than for the extratextual and historical elements. I was able to learn a lot about the era; about the portrayal of war before and during, how nationalities, their various struggles and how our enemies were represented for better or worse, the relationship between the government and Hollywood, and the image, propaganda and narratives that were being sold to the general public during an uncertain time of crisis. I highly recommend reading Thomas Doherty’s “Projections of War” and this year’s “Five Came Back” by Mark Harris (surely the best book you’ll read from this year).

The ratio of films I’d not seen before research versus films I’d already seen is quite different from other years I’ve done so far. While 4 of my 5 honorable mentions are new-to-me films, 8 out of the 10 on this list I’d seen before, and I revisited all of them for this list. This is also the most ‘typical’ list of the ones I’ve created so far. Most of these are quite well-known, at least within film circles.

1943 saw debuts from major filmmakers such as Akira Kurosawa (Sanshiro Sugata), Robert Bresson (Angels of Sin), Vincente Minnelli (Cabin in the Sky), and Luchino Visconti (Ossessione). This was my most exhaustive year in terms of re-watching everything I’d already seen from 1943. In particular I was able to get a lot more out of I Walked with a Zombie this time around, a film that left me unenthused when I first saw it several years ago. For all the polished message films about virtue and American democratic values, there’s a lot of grit, fatalism, and darkness to be found. You just have to watch the Val Lewton-produced films from RKO to see that.Lewton used the freedom of low-budget quickies as a template for innovative atmosphere and despairing messages. A new kind of horror happening right under everyone’s nose.

Everyone is looking for a culprit. There’s a lot of finger-pointing in 1943. Just look at Day of Wrath, The Ox-Bow Incident, Le Corbeau, and to lesser degrees Hangmen Also Die! and The Leopard Man. There were other ways of dealing with wartime in film as well; by not dealing with it. Already by 1943 audiences would be starting to get weary of the corny rabbles of patriotism, looking for pure escapist fare. The prime example of this is The Man in Grey, setting Gainsborough trend for tailor made bodice-rippers targeting female audiences on the British homefront. Being a big animation fan, I also took the time to watch a ton of cartoon shorts spanning mostly from Looney Tunes to Tex Avery.

Now to pay tribute to five films that did not make my final cut, all of which I highly recommend seeking out if you haven’t seen them already:

Angels of Sin (or Angels of the Streets) (Bresson) (France): Renée Faure gives an engagingly stand-out classical performance of conviction in Robert Bresson’s debut (his pre-formalist days) which equates nunneries and prison as places of protection and possible reform.

The Constant Nymph (Goulding) (USA): Rarely seen for seventy years due to legal rights, this flagrantly romantic film features a twenty-four year old Joan Fontaine uniquely capturing the awkwardness of adolescence and giving a career-best performance as Tessa. In many ways a companion piece and warm-up to Letter of an Unknown Woman with Fontaine playing a teen, tragic overtones, musician male leads, and the connectivity of music bringing it all together.

The Man in Grey (Arliss) (UK): A deliciously nasty piece of work, setting the standard template for the Gainsborough melodrama, a subset of films wildly popular with British female audiences during WWII for their aggressively escapist lasciviousness. Made me realize fully that I like my melodrama gnarled and perverse. Margaret Lockwood does wicked better than anyone.

Meshes of the Afternoon (Daren/Hammid) (US): A landmark experimental short and a touchstone of feminist filmmaking. Cyclical and symbolic, it represents the psyche in such unsettling and inventive ways. Teiji Ito’s music, added with the approval of Deren in 1959, is integral; the perfect companion of aural unfamiliarity to Deren’s images.

This Land is Mine (Renoir) (US):

Narrative propaganda that works, rife with talky preachiness that manages to strike a chord by stressing the importance of words and ideas against Nazi occupation. Charles Laughton’s transformation from mama’s boy coward to proud martyr is important, but George Sanders’s supporting arc as an informer and collaborator is even more important and resonant.

Biggest Disappointments:

Air Force

Cabin in the Sky

Watch on the Rhine

Jane Eyre

So Proudly We Hail!

Sanshiro Sugata

The Human Comedy

Lady of Burlesque

La Main du Diable

Blind Spots: (not exhaustive):

Portrait of Maria, Hitler’s Madman, The Song of Bernadette, Sahara, The Fallen Sparrow, For Whom the Bell Tolls, Journey into Fear, Hitler’s Children, Munchhausen, My Learned Friend, Destination Tokyo, Le voyageur de la Toussaint

Complete List of 1943 Films Seen: (bold indicates first-time viewings during research, italics indicates re-watches during research)

Air Force, Angels of the Streets, Cabin in the Sky, The Constant Nymph, Day of Wrath, The Eternal Return, Le Corbeau, Five Graves to Cairo, Flesh and Fantasy, The Gang’s All Here, The Ghost Ship, Hangmen Also Die!, The Hard Way, Heaven Can Wait, The Human Comedy, I Walked with a Zombie, La Main du Diable, Lady of Burlesque, The Leopard Man, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, The Man in Grey, Meshes of the Afternoon, The More the Merrier, Old Acquaintance, The Ox-Bow Incident, The Seventh Victim, Shadow of a Doubt, So Proudly We Hail!, This Land is Mine, Watch on the Rhine, Jane Eyre, Lumiere d’ete, Ossessione, Sanshiro Sugata, Stormy Weather

Shorts:

“A Corny Concerto”, “Red Hot Riding Hood”, “Who Killed Who?”, “Tortoise Wins by a Hare”, “The Wise Quacking Duck”, “Der Fuehrer’s Face”, “Falling Hare”, “Dumb Hounded”, “The Aristo-Cat”, “Scrap Happy Daffy”, “Pigs in a Polka”, “Jack-Wabbit and the Beanstalk”, “Education for Death”, “Chicken Little”, “Reason and Emotion”, “Wackiki Wabbit”, “Porky Pig’s Feat”

10. Day of Wrath (Dreyer) (Denmark)

Carl Theodor Dreyer’s first film after an eleven-year absence sees love regarded with corruption of the soul through religious persecution. This is material that in someone else’s hands might have read as rote or derivative. Its perspective is intimidating to parse through. My inability to get a grip on it guarantees its future value to me over the years. There’s an ambiguity to the proceedings as it suggests, through cross-cutting, that maybe Anne (Lisbeth Movin) does possess some kind of witchcraft (as in Ordet, higher forces or abilities are affirmed) as passed down by her mother. But it’s a separate issue; not placed in support of the religious persecution but seemingly vice versa, as if the power of suggestion initiates self-fulfilling prophecies. It complicates how we interpret the story, but not, critically, what happens within the story. In the end it doesn’t matter whether or not Anne has some unconscious power; the point is that that both possibilities would have led to the same place; Anne being targeted.

The pace is methodical and foreboding. Everyone moves with cautious intent. Anne is the odd one out (in many ways actually) intermittently trying to break out of the film’s rhythm with a hasty kind of half-prance. It’s a subtle and affecting way of showing how Anne has had the life sucked out of her before even having a chance to live, stripped down to devout duty. She comes to life as the film progresses, only to have it thrown back in her face. The softness of the birches contrasts the hardness of the austere interiors, with Lisbeth Movin’s face bridging the two by embodying both. As beautiful and alluring as the film is, it’s really Movin’s performance and general presence I connect with most in Day of Wrath. She has such a striking face, all archness and piercing eyes. Herlofs Marte (Anne Svierkier), a physical evocation of Anne’s mother, haunts the entire film after her fiery fate.

9. The Seventh Victim (Robson) (US)

This was a film I liked enough the first time I saw it but it didn’t live up to what I was hoping it’d be. I felt it was marred down by extraneous characters, a flat romance, underdeveloped relationships/knowledge of past relationships, and a group of elderly Satanists that don’t feel threatening at all. This time, while some of those issues haven’t gone away, the message of the piece and what it turns out to be is downright audacious, casting only the kind of spell that Val Lewton’s RKO cycle can lay claim to. Mark Robson’s debut shows he can hold his own with Jacques Tourneur, having learned the ropes well from his editing work with him and Orson Welles.

The Seventh Victim plunges into the depths of melancholia, the inescapable pull of death. It’s a sort of horror film noir packaged in a detective story. Its philosophy, which Lewton admitted flat-out, is to embrace death. It’s a shocking statement, one that RKO only gets away with because the film wasn’t top brass enough for anyone to take notice. The Satanists are not the enemy. They are an empty placeholder, an unsuccessful attempt by Jacqueline (Jean Brooks) to find meaning within the darkness. They are similarly desperate, a mundane and hypocritically confused group. Jean Brooks, in an iconic role, dons a fur coat and jet black hair severely framing her face; protective shields against the world.

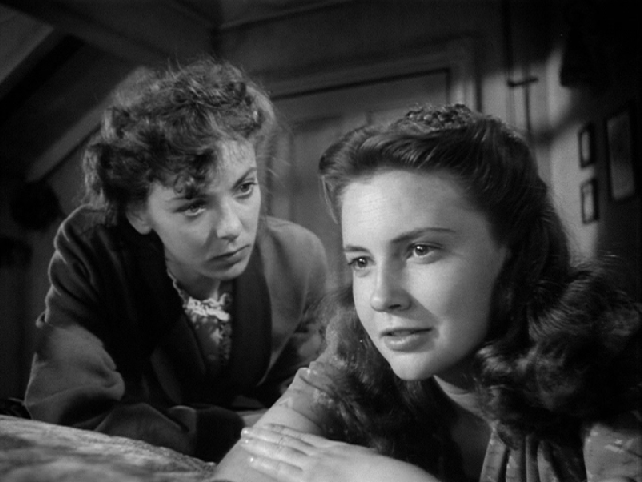

Kim Hunter, in her film debut, travels from the safe confines of echoing Latin and stained glass to the New York jungle. Her sisterly connection with Jacqueline is spoken of, never felt. Jacqueline is too far gone to the other side, their experiences too dissonant. There’s a real hopelessness to how little exists between them once they’re finally brought together, purposeful or not.

There’s a point midway where the story is plagued by unanswered questions and you think ‘what in the fresh hell is going on?!’. Like something out of the mind of David Lynch. On the surface it’s guided by Hunter’s search, but she and the film are actually guided by Lewton and Robson’s symbolic imagery; hanging nooses, locked rooms, and staircases. There’s even a pre-Psycho shower scene, but instead of murder, vital information is passed between women through curtains, shadows, and nakedness, lending to the lesbian undertones.

Jacqueline’s perspective takes over for the final twenty minutes, and it’s the film’s big takeaway. We realize Kim Hunter, the poet, and the husband have been a means to an end. Her famous walk through the streets, fleeing from her pursuer, is a walk of the mind. She resists but it’s futile. Her search for a light at the end of the tunnel is conveyed through the lighting, the unwanted bacchanal celebrations of a theater troupe her only undesirable out. And then there’s that profound exchange with Mimi (Elizabeth Russell), a dying specter who makes herself known at the very end. The scene stops me dead in my tracks. Mimi runs towards a last burst of life. Jacqueline limps resignedly towards death. They meet in the middle. The Seventh Victim may look like it’s about missing sisters and Satanists, but it’s not. To Die, Or Not To Die. That is the question.

8. The Hard Way (Sherman) (US)

One of the best rags-to-riches showbiz claw-my-way-to-the-top yarns with older sis making sure little sis’s dreams of performing on the stage are realized. They rise up from an unhappy marriage, grey dowdy graduation dresses, and endless soot to contracts, furs and success.

Ida Lupino’s eye-on-the-prize performance is electric (though she apparently was not fond of her work here), constantly looking for ways out and up, unabashedly seizing upon questionable opportunities that present themselves, gradually unable to tell the difference between success and personal happiness. Joan Leslie is equally good, like a 40′s Jennifer Jason Leigh (with a dash of Larisa Oleynik?). She is increasingly torn and devastated, loyalty in check far past its expiration date.

And the two male counterparts, played by Dennis Morgan and Jack Carson, are just as engaging! Not something a lot of female-led films of 1943 can lay claim to. Paul (Morgan) sees through Helen and the two have a great dynamic as she tries to suppress feelings for someone who loathes yet admires her. Al (Carson) is an earnest and naive schlub whose pride and blinders prove too much. What I loved most about The Hard Way is the careful and complicated evolution between all four characters, with attention paid to who they are within themselves and in relation to each other through time as paths cross and double-cross. There’s a development in Act 2 that completely took me off guard. The direction and staging enhance our understandings of the character dynamics and includes visually stimulating and slightly surreal montage sequences.

7. The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (Powell/Pressburger) (UK)

Are you starting to get a sense of how packed this list is?

It takes some time, at least I find, to get on the wavelength of The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. It’s a treaty on what it means to be British, more specifically in wartime. Between that and its microscopic deconstruction of societal rituals it can be hard to engage with it at first. Then it gradually becomes more attachable, and long after it’s over it feels like a warm blanket (especially when Deborah Kerr is onscreen) that drapes itself over you, that effervescent Powell/Pressburger touch. It’s not entirely a comedy, a drama, or a war film. It’s all three with dashes of fantasy and dreamlike flourishes, most notably Kerr’s three character performance as the evolving youthful woman through the ages, going in and out of the lives of Clive and Theo through the decades. Re-watching this and Heaven Can Wait for this list, it’s interesting that, despite their similarities, the former spans seventy years of life removed from history, and the latter spans forty years of history through people. It’s less concerned with how others are during war, instead asking how the collective British ‘we’ functions as a people during conflict. It’s patriotic, but not blind, swerving in more ways than one from what British cinema tends to be. It’s lavish and heightened, and also dares to feature a sympathetic German as a central character during WWII.

Speaking of Anton Walbrook, he’s such a favorite; one of the sexiest and most arresting actors to watch. Will someone just have an Anton Walbrook marathon with me where we watch all of the films? His speech, which serves as the film’s nucleus, is one of the most encompassing speeches I’ve ever seen. All in one take, almost two decades of personal history summed up in the afterglow of loss. He slowly summons the attention of everyone in the room, and of us. Powell films the speech all in one take, with an invisibly slow push-in. By the end, we’ve lost time from falling into Walbrook’s eyes and words.

Powell is brilliant at staging scenes; blocking and shot choices contain voluminous treasures. The beer hall scene is a perfect example of his precision. Everything, from the use of Technicolor to the film’s intricate structure, courtesy of Pressburger, is precise and dignified without being stuffy. The way time passes, with the big game hunting montage and the browsing of an intimate photo album, are by turns witty and weepy.

Traditional British values are mourned and tribute is paid to the importance of ritual by putting them front and center. Notice how we go through all the preparation for the duel only not to see it. But it’s not a simplistic ‘Remember the way things used to be’ story. We learn and see what Clive can’t; that right is not might. Unlike Clive, the film acknowledges the necessity of change for better or worse. Clive is always one step behind himself, realizing his love for Edith too late. You can clearly see the moment he realizes. It’s heartbreaking, especially because Edith has also been torn, looking for a sign from him. The scenes with Clive, Edith and Theo in the hospital are my favorites. A growing camaraderie and kinship emerges between the three, a bond that comes to exist again but in a much different form, and never fully regained.

6. The Leopard Man (Tourneur) (US)

It’s the structure of The Leopard Man that leaps out at you, so ahead of its time, postmodern to the point where even today it’s still somewhat jarring to see a film led entirely by fate. Clo-Clo (Margo), oblivious harbinger of doom, brushes past the lives of eventual victims (thereby controlling the narrative) who we proceed to follow. The film has uncommon empathy for its victims, so much so that it dictates structure and content. These women are made human before death, given context and individual meaning.

The scenes of moonlit pursuit produce some of Jacques Tourneur’s strongest work. The most chilling moments? My vote goes to those immediately proceeding death when the pursuit stops and everything is still. The banging of the door and subsequent blood seeping underneath, the weight on the branch, the mirror closing and Clo-Clo’s desperate screams. Then there are Clo-Clo’s clickety-clacks, which we eventually recognize as the sound of death. The film neatly fits in with Tourneur’s fatalism. The fountain with its floating ball, guided and held up by something bigger than itself; not a higher being, but inescapable circumstance.

The killer’s identity is clear pretty early on, but it’s notably only when the first death occurs, the one committed by the frightened and threatened leopard, that Galbraith opens himself up to opportunity and urge. That “kink in the brain” addresses the makeup of a killer with animal instinct (as predator, not killer for sustenance or out of fear), connecting leopard and man thematically as opposed to the forced RKO title of ‘The Leopard Man’. The events may cause the central couple we repeatedly return to to ‘go soft’ but they cause Galbraith to go hard, giving in and letting go.

5. The Ox-Bow Incident (Wellman) (US)

It’s never a mystery whether the three men in the hands of a vengeful posse actually killed Larry Kinkaid. It’s clear they didn’t. The point is casting a judging eye at vigilantism, revenge for revenge sake, and the unapologetic out-for-blood mentality of an angry mob that swiftly ignores law. Relatively speaking, it’s an easy point to make. Just like the mobs themselves, films like this are never subtle. But The Ox-Bow Incident is a sort of marvel all the same. It’s pure emotive power is raw and kind of overwhelming by the end. The cumulative impact of injustice creeps up on you. The senselessness of it. And that Kinkaid isn’t even dead? Forget about it. It’s an unforgiving film; enraged and resentful.

It’s surely one of the most efficient films ever made. Clocking in at seventy-five minutes, screenwriters and filmmakers could still stand to learn a lot about storytelling from The Ox-Bow Incident. It manages to introduce and juggle about a dozen characters, all of them distinct, even those operating within caricature. They are one body broken apart into individual participants by the script. Gil and Art (Henry Fonda and Harry Morgan) are our entry point. They start out with their own hang-ups and are gradually drawn into the scenario that unfolds before them. Fonda’s Gil is a despondent man, his character coming through strongly despite this not being his story. Anthony Quinn’s presence injects some commentary on racism; Juan is entirely unsurprised by the events. He knows enough about people, and the way he’s likely been treated in life, to know they won’t get out of this one. And Dana Andrews. Poor terrified Dana Andrews, openly scared of dying and of leaving his wife and kids. The camera crunches him in more than anyone.

William Wellman had to fight a long time for this to get made, the compromise being that Darryl Zanuck threw it into the cheap pile. The resulting artificial sets mandate Wellman’s direction. He shifts focus away from the flat landscape and onto people and their faces. Ugly, hankering faces. People are constantly crammed on multiple planes within compositions. It’s so claustrophobic, the camera creating boundaries for people who have none. The mob puts the men on ‘trial’ while the camera in turn puts the mob on trial.

4. The Gang’s All Here (Berkeley) (US)

Busby Berkeley, taking on Technicolor, pushes the visionary of geometric extravaganzas as far as he, or anyone in the studio era, was apt to go. Color is used for grand elegiac expression, such as the “Paducah” under an encompassing lavender swirl that predates what An American in Paris would do with dancing and color eight years later. The camera, and the effects work, is periodically used to disorient, heightening our sense of movement and curiosity to a drug-inducing degree. Eugene Pallete’s disembodied head croaking out a song. A camera that arches and lilts over women holding sexualized bananas. The mere fact that a number called “The Polka Dot Polka” serves as a finale with women in purple outfits that look like futuristic workout gear holding neon-pink lit hula hoops.

It’s also, quite simply, a lot of fun despite a central storyline that can exhaust with boredom. Although it must be said that Berkeley himself seems to view it as filler. What makes up for this is that Alice Faye grew on me, that James Ellison is blissfully absent for the entire second act, and that their romance is amusingly resolved with barely a shrug, an afterthought that clearly doesn’t deserve center stage when there are polka dots to be had.

Carmen Miranda is Queen. It’s taken me this long to actually see her in a film. A lot can be said for the ways in which her nationality was used as a gimmick as well as a garish ‘foreign’ stereotype, but what about what’s actually there? How about the performance and the work and the fact that she was able to secure a spot for herself within the studio system where every other star also, it must be said, had a minutely constructed screen persona. Miranda is vibrantly hilarious here, with an innate sense of comic timing, over-the-top in every moment (not just when she has dialogue), with the English language locked-and-loaded as her plaything (notably mainly restricted to our idiosyncratic sayings, not the foundation of the language). To say she steals the movie is an understatement. Berkeley sets up a world where the more heightened the better; a world fit to hold and showcase Miranda at the center. She is the purest harbinger of future camp and drag queen aesthetic and performance in the 1940′s.

Charlotte Greenwood, hip society matron and proto-Marcia Wallace with high-swinging legs is another favorite.

3. Le Corbeau (Clouzot) (France)

A particularly unsparing look at humanity and our ability to turn on each other, Le Corbeau has been dirtied by history from the day it exited the womb. Made by the German funded Continental Films, Henri-Georges Clouzot was banned from making films until 1947 (lifted from its initial lifelong stamp). It was seen as Anti-French at the time it was made, it is now seen in a more Anti-Nazi light and more broadly an Anti-People light. The misanthropy is locked and loaded even though room is made for people to find each other and for the guilty to go punished.

Le Corbeau addresses the power, cowardice and impact of omnipresent anonymity in a small town that collapses like a house of cards as secrets are exposed within the community. Someone is watching. Everyone is being watched by one of their own. Dark humor is found in the recesses and hypocrisies of a town thrown unto upheaval. The power of the letters is constantly given weight by Clouzot. During a funeral procession, a letter is seen in the road by everyone who passes. Nobody will pick it up; they avoid it like the plague, acknowledging its hold on them through nervous neglect. There’s even a letter point-of-view shot as everyone steps around it, a child eventually picking it up. Then there’s the shot of the letter floating down from the rafters of the church. It’s a perfect, almost pitiful evocation of how beholden the townspeople are to their own secrets. The world Clouzot depicts feels so insular and gradually uncontrollable in its futility, most notably during a sequence in which the accused Marie flees from the crowd. Shots become exaggerated and canted, sound becomes chaotic and inescapable. It’s the film’s most blatant callback to German Expressionism.

Poison pen letters would suggest based on immediate assumptions, a female culprit. But it’s not, not really, and the women of Le Corbeau are an atypical group who flip-flop expectations at every turn. I love that Denise, presented as a supporting suspicious sexpot, is ultimately presented as good, even inheriting the role of romantic lead. Her physical ailment leaves her clamoring for sexual affirmation, a need to assert herself while simultaneously listless and feigning additional illness. The nurturing Laura, a woman who seems destined for better things, is at once duplicitous and a victim. The vengeful mother, executor of justice, takes matters into her own hands, and is the one to restore the natural order. How are we meant to feel about that final act? It’s up to us. The final shot sees her as a floating faceless figure, slowly disappearing down the narrow alleyway without a trace, leaving the crime scene in our dirty hands.

2. Shadow of a Doubt (Hitchcock) (US)

Easily the film I’m most familiar with on this list, having seen it many times. More misanthropy! This time with Joseph Cotten’s Uncle Charlie. “Did you know the world is a foul sty?” Listening to him, he’s a kind of murderous Eeyore. The idealized duality, which Hitchcock emphasizes in many ways including how the two are introduced, that Charlie imagines between her and her uncle is completely shattered. It’s about two sides of the same coin, the innocuous (not just with Charlie’s small-town boredom but with how Joseph and his friend lightly but minutely discuss murder; it’s abstract and distant for them, a part of other people’s stories) going head-to-head with its opposite.

Shadow of a Doubt is also importantly about the nature of family, and what happens when the veil is lifted on someone you thought you knew; someone who you are bonded with by blood. Not only all that, but someone you put all your hopes and dreams into. This is where Hitchcock gets all the suspense; by understanding that the central tug-of-war is the discrepancy between who Charlie and the family think Uncle Charlie is and who he actually is. Visual and aural cues like the emerald ring, the waltz, and the newspaper are so the audience, we at the top of the information hierarchy, can brim with tension from start to finish.

Joseph Cotten is menacing as Uncle Charlie, seething with disgust all around. Cotten also lends a depressive edge to his performance, hinting at something unquenchable. There’s also a bit of sexual tension between the Charlies. Hitchcock and screenwriters Thornton Wilder (!), Sally Benson, and Alma Reville inject such salty eccentricity from top-to-bottom. This may be a thriller, but there’s so much trademark humor to be found (mostly character based) from Hume Cronyn offering Henry Travers hypothetically poisoned mushrooms, to the precocious Ann. Small-town life is gently poked at with a loving touch. The rug isn’t pulled out from under Charlie to throw her so-called woes in her face, but to make her appreciate the family she has right in front of her.

1. The More the Merrier (Stevens) (US)

I’m just head over heels in love with this movie, which takes the then-serious housing shortage in Washington D.C during the war and makes a screwball comedy out of it! The More the Merrier marks George Stevens’s last foray into comedic territory. He left immediately after the film’s completion to join the U.S Army Signal Corps, and his experiences during the war would dramatically shift the kinds of films he’d be making thereafter. This is one of the sexiest romantic comedies of the studio era. In fact it’s damn near erotic. It hilariously scrutinizes how our trio in close quarters shares space from the sitcom-esque sequence with the hectic schedule, the crowded closeness of the premise, and Jean Arthur’s increasing loss of control in her own home.

Stevens often shoots from outside the apartment looking in, using the windows as frames within frames, closing the characters in with each other and using the same techniques to bring them harmoniously together whether they like it or not. This brings the audience into the equation, involving us in the intimacy between Jean Arthur and Joel McCrea. The three leads are magnificent, career-best work from all. Jean Arthur is smoldering through her character’s button-cute type-A way. Joel McCrea is impossibly sexy, the opposite of Arthur in his quiet flirtatiousness and at times childishness. Charles Coburn, in an Oscar-winning role, could have been a sentimental eccentric old coot, but the writing and performance make it so much more. The dynamics between the three are so organic and joyous to watch unfold, especially the way factions within emerge such as the antagonistic boys club versus their target Arthur.

And that eroticism I mentioned earlier between Arthur and McCrea? Oh, it’s there. Just look at the scene when he gives her the suitcase, his face close to hers, showing her all the compartments. Or the long take starring Body Language with the two strolling down the street. It doesn’t get sexier than this sequence folks. Like, I think I stopped breathing during it. It’s a dance between the two. He’s outright pawing at her, she’s being coy. What are they talking about? Is anyone even listening? I don’t even know how this all got past the censors, because once they sit on the steps he starting feeling her up, his hand obsessing over her face, neck, and shoulder. Mein Gott. Or that bedroom scene, with the camera bringing the two bedrooms together as they longingly lust after one another in their separate beds. The two actors have a special onscreen connection. In an early scene, the two dance in separate spaces with themselves, the camera linking them in their adorable awkwardness. Then in a later scene, the two sit across from each other at dinner with Coburn and Arthur’s fiancee. Sharing a private moment unbeknownst to the other two, they stare at each other moving their shoulders and body ever-so-slightly to the music. The sly cuteness of it all is too much.

But what about that ending? I’d love to hear what others think of it because it leaves me with a sad and peculiar taste. It uses the WWII movie trope of the quickie marriage and then settles the couple into a tired marriage with lots of Arthur wailing. That this is my favorite film of 1943, despite going off-center in its finish, goes a long way in conveying just how much I’m in love with this film.